Poster of the exhibition Congo as Fiction

Museum Rietberg Zurich, 2019/20

Shadow of Hans Himmelheber in a Tipoye

DR Congo, Yaka region, 1938

Cellulose nitrate

Museum Rietberg Zurich, FHH 155-26

Donation of the family of Hans Himmelheber

Interview with Sammy Baloji and other artists in the exhibition Congo as Fiction (part 3)

Museum Rietberg Zurich, 2019/20

Sammy Baloji

Installation Kasala: The Slaughterhouse or Dreams of the First Human, Bende's Error - view in the exhibition Congo as Fiction

DR Congo and Belgium, 2019

Mixed Media

Museum Rietberg Zurich, 2020.272

Acquired with funds from the City of Zurich

Artist of the Luba region

Figure of a seated woman with bowl, mboko

DR Congo, before 1938/39

Wood, glass; 28.5 x 17.2 x 17.5 cm.

Museum Rietberg Zurich, 2018.1109

Donation of Eberhard and Barbara Fischer

Sammy Baloji

Residence in Congo, 1956 (Archive E. Lebied, InforCongo Tervuren, AfricaMuseum Tervuren) - part of the installation Kasala.

DR Congo and Belgium, 2019

Museum Rietberg Zurich, 2020.272

Purchase with funds from the City of Zurich

Sammy Baloji

Hunting horn made by the coppersmith Guido Clabots - part of the installation Kasala

Copper; 40 x 66 x 25 cm

DR Congo and Belgium, 2019

Museum Rietberg Zurich, 2020.272

Purchase with funds from the City of Zurich

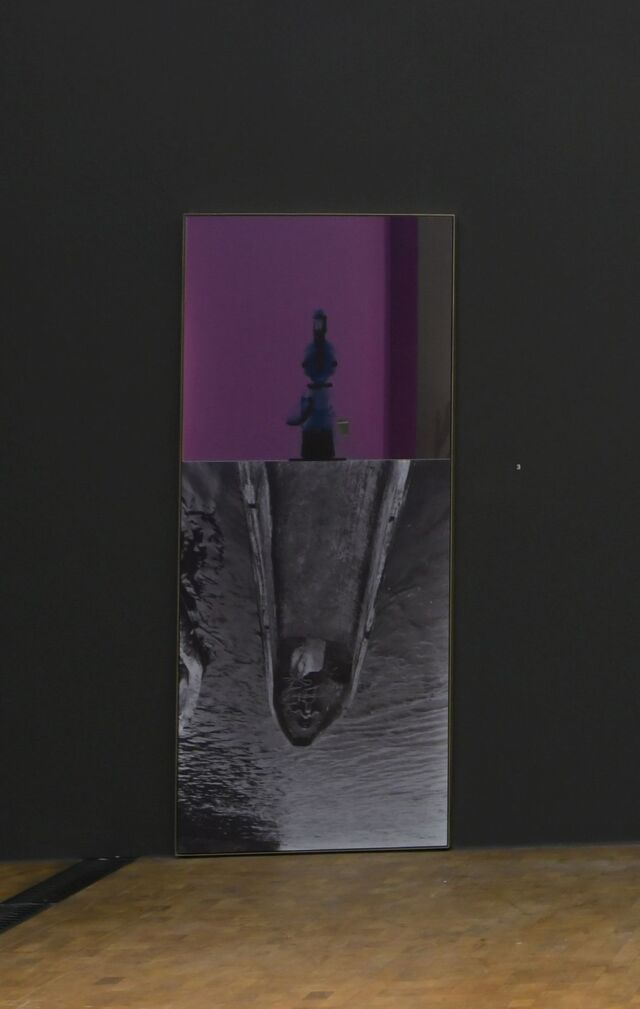

Sammy Baloji

Mirror with photographs by Hans Himmelheber and X-Rays of power figures - part of the installation Kasala

Glass, wood; 204 x 83 cm

DR Kongo and Beglium, 2019

Museum Rietberg Zurich, 2020.272

Purchase with funds from the city of Zurich

Artist and ritual expert of the Congo region

Power figure with mirror, nkisi

DR Congo, early 20th c.

Wood, clay, glass, iron; 23 x 8.5 x 13 cm

Museum Rietberg Zurich, RAC 712

Donation by Eduard von der Heydt

Performance Kasala by Fiston Mwanza Mujila, Patrick Dunst and Grilli Pollheimer at the opening of the exhibition Congo as Fiction

Museum Rietberg Zurich, 2019

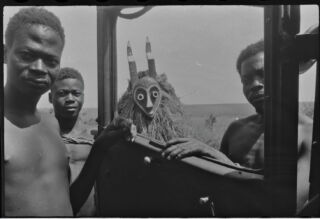

Hans Himmelheber

Mask of the Pende region looking into Himmelheber's car

DR Congo, Pende region, 1939

Cellulose nitrate

Museum Rietberg Zurich, FHH 190-37

Donation of the family of Hans Himmelheber

Hans Himmelheber in the tipoye

DR Congo, 1938/39

Cellulose nitrate

Museum Rietberg Zurich, FHH 176-8

Donation of the family of Hans Himmelheber

Hans Himmelheber

Figure on the car of Hans Himmelheber

DR Congo, 1939

Cellulose nitrate

Museum Rietberg Zurich, FHH 186-3

Donation of the family of Hans Himmelheber

Hans Himmelheber

Port of Kinshasa

DR Congo, 1938

Cellulose nitrate

Museum Rietberg Zurich, FHH 160-5

Donation of the family of Hans Himmelheber

Hans Himmelheber

St. Anne Catholic Church in Kinshasa

DR Congo, 1938

Cellulose nitrate

Museum Rietberg Zurich, FHH 161-25

Donation of the family of Hans Himmelheber

Hans Himmelheber

Monument des aviateurs in Kinshasa

DR Congo, 1938

Cellulose nitrate

Museum Rietberg Zurich, FHH 160-21

Donation of the family of Hans Himmelheber

Artist of the Luba region

Lukasa memory board

DR Congo, 20th c.

Wood, metal, glass, 12x56x30 cm

Museum Rietberg Zurich, 2023.306

Purchase with funds of the city of Zurich

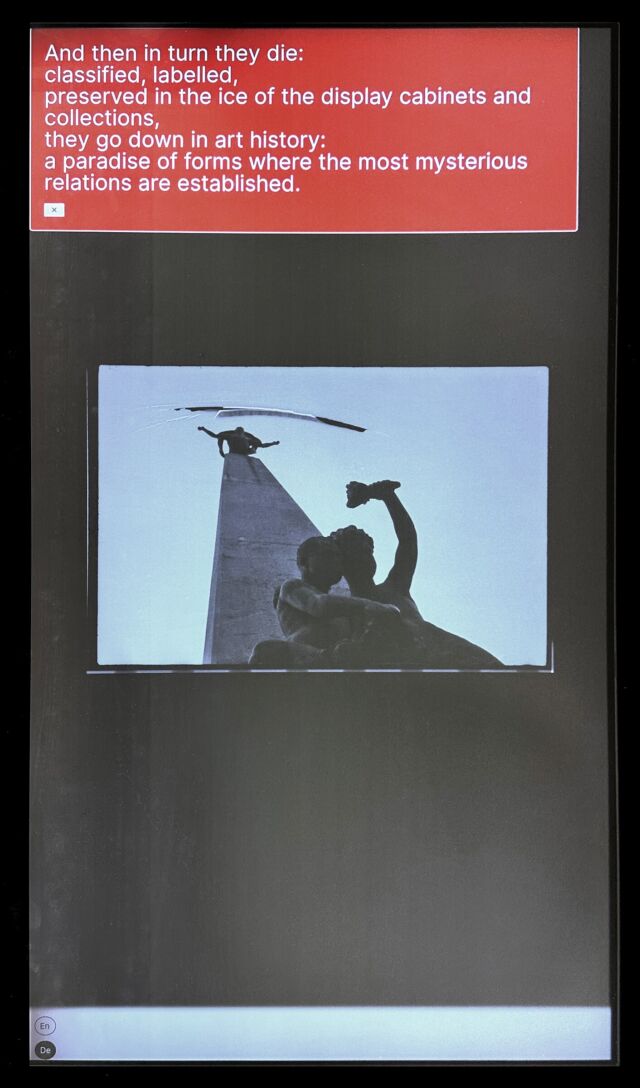

Sammy Baloji

Touchscreen - part of the installation Kasala

DR Congo and Belgium, 2019

Mixed media

Museum Rietberg Zurich, 2020.272

Purchase with funds of the city of Zurich

Sammy Baloji

Touchscreen - part of the installation Kasala

DR Congo and Belgium, 2019

Mixed media

Museum Rietberg Zurich, 2020.272

Purchase with funds of the city of Zurich

Sammy Baloji: Kasala as a New Way of Reworking Archives

Michaela Oberhofer

09.10.2023

During an artist residency, the Congolese artist Sammy Baloji asked himself: «How do you decolonize yourself?»

Born in Lubumbashi in 1978, Baloji has been working with colonial archives for almost twenty years. As founder of the Biennale in Lubumbashi and the artist collective Picha, he also created new structures and spaces of participation in the Congolese art scene. In 2019, he was involved in the exhibition Congo as Fiction at the Museum Rietberg in Zurich. The exhibition was part of an ongoing research project around the archive of the German art anthropologist Hans Himmelheber. It focused on his research and collecting trip to the Belgian Congo in 1938/39. During his sojourn, Himmelheber took almost 1,500 photographs and acquired approximately 3,000 objects, some of which are now in the Rietberg Museum.1 Sammy Baloji was part of the artist program in which six artists from the DR Congo and the diaspora were invited to engage artistically with the colonial archive of Hans Himmelheber.

In an interview made for the exhibition, Sammy Baloji questioned the extent to which the curatorial, scholarly and artistic research of this archive can be understood as a process of decolonization. On the one hand, he analyzes his own artistic approach to deconstruct colonial archives and reacts to them with new methodologies and counter narratives. On the other hand, Sammy Baloji addresses his question «How do you decolonize yourself?» to the museum and its visitors, as well as to our research and curatorial team. It is a call to question the historical origin of Himmelheber's archive and its embeddedness in the colonial era, but also, to critically reflect on the still existing imbalance of power and epistemologies in today's academic and museum theory and practice.

The name Sammy Baloji chose for his installation in Congo as Fiction reflects the multiple layers of meaning of his artist research which is also a long-term project at Sint Lucas Fine Art University in Antwerpen. Kasala: The Slaughterhouse of Dreams or the First Human, Bende's Error is a remix of different techniques and medias ranging from photography, collage and video to sound, performance arts and even IT technology. In his installation, Baloji overwrites Himmelheber's colonial archive with alternative meanings and stories. In doing so, he developed new methods that drew on local narratives and memory practices of Luba culture, based on performative practice and oral history (see his keynote at the conference “Reworking the Archives”).

During his 13-month research and collecting trip through Belgian Congo in 1938/39, Hans Himmelheber travelled through the northern and eastern settlement area of the Luba groups in the Kassaï region. His journey, however, did not take him to the southern Luba settlement area in the Katanga region. In his diary, he described how severely the Luba people were affected by colonization, missions, migration, and the plantation economy. This had an impact on all areas of life – from architecture and agriculture to material culture. In the 1930s, European clothing was already predominant, and dwellings had also changed. As a collector and trader, Himmelheber was particularly disappointed by the «destruction of indigenous art by the missions», and he was able to acquire but a few objects of the «good old Baluba art».2 At the Katombe Mission, he learned that «one of their missionaries had burned the masks by the dozens throughout the country».3

With his installation Kasala, Sammy Baloji addresses the effects of colonial extractivism described by Himmelheber. Kasala thus shows how much the exploitation of humans, animals, art, and nature was and is interwoven. One aspect is the decimation and even destruction of wildlife in Africa by big-game hunting since colonial times.

The starting point of Baloji's installation is a reproduction of a 1950s black-and-white photograph from the colonial archive of Tervuren, showing the bourgeois interior of a private residence in the Belgian Congo. The Europeans depicted are visibly enjoying the family atmosphere in a room whose walls are decorated with hunting trophies of buffaloes and antelopes. In the center in the background hangs a hunting horn, a symbol of the violent practice of exploitation.

By analogy, Sammy Baloji had a hunting horn made by a Belgian blacksmith and placed it in a display case in the center of his installation. As he mentioned, the instrument on display in the museum has fallen silent and can only be perceived aesthetically. The copper of the horn is an allusion to the extractivism in the copper mines of his home region Katanga. Similar to his series Société Secrètes (2015), the surface of the instrument is ornamented with abstract patterns, reminiscent of scarification in Congo body art associated with initiation rituals, identity and social belonging in pre-colonial times.

In this sense, the installation Kasala is also an allusion to Baloji’s work Hunting and Collecting (2015). The hunting of big game by European travelers and collectors is equated with the «scramble» for African art. In both cases, the act of violent appropriation results in something that is no longer alive or active – whether an animal trophy on the wall or an object in a museum.

In his installation, Baloji addresses the translocation of objects from Africa that are deprived of their cultural meaning and displayed in museums as works of art. He literally holds up a mirror to museums and visitors: the lower half of two large mirrors is covered with photographs taken by Himmelheber, while the upper half is printed with X-Ray scans of power figures from the Songye and Pende regions that were displayed in the exhibition Congo as Fiction. Ritual experts charged minkisi power figures with supernatural powers to protect individuals and communities. Baloji poses the critical question of how legitimate and ethically correct it is for museums to undertake a scientific analysis of sacred objects and reveal their hidden inner world through visual technology. With the mirrors, the artist also alludes to the materiality of minkisi power figures themselves: besides incorporating animal, vegetable, and mineral substances, minkisi were also equipped with fragments of glass and mirrors imported from Europe. The mirror on the abdomen was a kind of compass indicating to the ritual expert the direction from which disaster threatened. In a further development of Kasala shown in the Galerie Imane Farès 2020 with a text by Lotte Arndt, Baloji equates the X-Ray scans of objects with the transillumination of precious earths such as citrine crystals from the mines in Katanga.4

In his interview for the exhibition Congo as Fiction, Sammy Baloji stated that the translocation of objects from their original context to museums leads to a process of decontextualization in which intangible values and knowledge about the use and cultural meaning are irreversibly lost. For Baloji, museum objects no longer have a religious dimension: «I don't feel any spirituality; we can't fetichize them today outside the aesthetical thing we give to them. It is a tricky situation: how are we making sense of something that is no longer significant?»

In his installation, Sammy Baloji gives these silent and meaningless objects a voice again, uncovers their hidden stories and creates new meanings and methods. At the inauguration of the exhibition Congo as Fiction, he collaborated with the author and poet Fiston Mwanza Mujila who composed a so-called kasala for him. He performed it with the jazz musicians Patrick Dunst and Grilli Pollheimer. The lyrical text and emotional performance were a modern interpretation of a kasala, a particular form of poetry and praise song practiced in the oral tradition of the northern Luba region. Members of the Mbudye group recited these memorial poems at funerals and other festivities. They referred to important historical moments or the genealogy of important heroes and evoked emotions and nostalgic memories in the audience.5 In his new kasala, Fiston Mwanza Mujila tells the fragmented story of the miners' protests and uprisings in Katanga that were crushed by government troupes. This event is symptomatic of the political unrest and uprisings in Congolese history until modern times. The first man, ancestor and creator of the world named Bende had to witness how the world was transformed into a «slaughterhouse» due to colonization and its consequences up to the present.

For the exhibition, Sammy Baloji combined these painful stories of the modern kasala with historic images from Himmelheber's photographic archive and displayed them on an interactive touchscreen for the visitors. On the one hand, he inserted selected photographs of emblematic mask performances or portraits of villagers such as Himmelheber used for his fiction of a supposedly «traditional» rural Africa. On the other hand, Baloji also included images documenting Himmelheber's mode of traveling, either in a tipoye or later in a car, which enabled him to travel further and acquire even more objects.6 The photos reflect Baloji's reading of the archive in highlighting Himmelheber’s colonial gaze and his activities as art trader.

Aware of the effects of colonization, Baloji also selected photographs of the colonial infrastructure of Kinshasa which Himmelheber took rather incidentally and never published. These include the harbor with cargo ships, the Catholic cathedral St. Anne built in 1913 and the Monument des aviateurs, dedicated to three Belgian pilots who maintained one of the first airlines between the colony and Belgium and died in a crash in 1923.

The interactive touchscreen itself is another reminiscence of historical forms of historiography among the Luba. It alludes to a lukasa, a wooden board with figures on which glass beads, pieces of wood, but also screws, nails and other metal objects were arranged. Such memory boards were used by the southern Luba to remember individual passages of Luba history and mythology by means of the small elevations.7 While history is remembered through writing, photographs, or monuments in Western societies, the Baluba's mnemonic techniques were linked to oral history and performative practices. By bringing together kasala and lukasa in his installation, Sammy Baloji reunites different forms of memory practices of northern and southern Luba in the Kassaï and Katanga regions and thus creates a new living archive and storage medium of remembrance.

The digital touch screen is a reference to modern communication with smartphones. With the traditional lukasa and Baloji's touch screen, visitor’s’ fingers create new narratives, images and memories. Just as visitors can rearrange their own kasala on this modern lukasa, an ongoing memory-making with modern techniques takes place with smartphones. At the same time, the IT technology and materiality of the hardware refer to the extractivism of valuable earths such as coltan, which are mined in the Congo and used for global digitalization.

Of course, there is not only one answer to Sammy Baloji's question of how to decolonize oneself. With his multimedia installation Kasala, the artist refers to the early colonial-critical film Les statues meurent aussi (1953) by Alain Resnais, Chris Marker and Ghislain Cloquet. For his contribution to the catalogue Congo as Fiction, Baloji chose a passage containing the following sentence: «An object is dead when the living gaze on it has disappeared». Sammy Baloji's artistic work aims to end or reverse this process and give a new voice and meaning to the silenced objects and hidden stories in museums – to enable a new living engagement. To do this, he creates new narratives and methodologies that build on the painful colonial history of the Belgian Congo and blend it with modern interpretations of memory practices from his own family history.

1

See also Guyer, Nanina: "Factual Moments, Visual Fictions: Notes On The Creation Of Hans Himmelheber’s Congo Photographs" and Oberhofer, Michaela: "Between Researching and Collecting: Hans Himmelheber In The Congo, 1938/39". In Nanina Guyer and Michaela Oberhofer (eds.): Congo as Fiction. Art Worlds Between Past and Present. Zurich: Museum Rietberg / Scheidegger & Spiess, 2019.

2

Himmelheber, Hans: Unpublished article in Brousse, pp. 5 and 12, Translation of the author.

3

Archive Museum Rietberg, Diary of Hans Himmelheber, 5 May 1939.

4

See also Lotte Arendt on Lukasa, 2020.

5

See Nooter Roberts, Mary and Allen F. Roberts (eds). Memory. Luba Art and the Making of History. 1996.

6

Oberhofer, Michaela: "Between Researching and Collecting: Hans Himmelheber In The Congo, 1938/39". in Nanina Guyer and Michaela Oberhofer (ed.): Congo as Fiction. Art Worlds Between Past and Present. Zurich: Museum Rietberg / Scheidegger & Spiess, 2019.

7

See Behrend, Heike. "Lukasa: Erinnerungstafel im Luba-Königtum". In: Pethes, Nicolas and Jens Ruchatz (eds). Gedächtnis und Erinnerung. Ein interdisziplinäres Lexikon. 2001: 359.